A team of researchers from Penn State Smeal College of Business published the Journal of Operations Management report, noting that consumers are willing to pay more money for clothes they can customise and keep for longer.

The findings suggest that clothing companies that adopt a mass customisation model can remain profitable while decreasing the fashion industry’s environmental impacts.

Dan Guide, Smeal chaired professor of operations and supply chain management, believes the question is finding a way to provide product variety while not suffering significant cost on initial manufacturing expenses.

He says: "The big idea is that we'd like for people to stop disposing of stuff as fast as they do."

What does the research say?

One of the report's authors, Aydin Alptekinoglu who is a professor of operations and supply chain management, explains: "We hypothesised and showed that providing customisation to cater for individual consumer tastes but at a mass scale — the idea of mass customisation applied to fashion — might help delay the eventual disposal."

He continues to say that mass customisation can be the basis for a new business model in fashion that is more sustainable and more profitable.

To test the business model, the researchers conducted a pre-test, followed by two studies to investigate consumers’ reactions to varying degrees of the mass customisation of T-shirts.

In the first study, 237 undergraduate students were randomly assigned to participate in person, where the team examined the effects of four customers’ involvement points — design, fabrication and use — on their willingness to pay for and hold on to the T-shirts.

They had the option to either opt for ready-made T-shirts or alternatively, personalise them by selecting from a range of existing colours and images provided by the firm. There was also an option for more extensive customisation where the customers could create their own custom colour and select from the firm's library of pre-existing images or "fabrication."

The final level of personalisation called "design" meant the customer could create a completely unique T-shirt by customising the colour and image.

In the second study, the focus shifted to exploring different approaches to a single point of customer involvement in mass customisation. For this, 501 US participants were included and randomly assigned to give different groups representing distinct customisation conditions.

The researchers highlighted the idea was to specifically investigate the influence of providing sample images in the design condition on how much the participants would pay for and how long they would keep the customised products. By randomly allocating participants to one of these conditions, researchers could test how different aspects of customer involvement affect the overall mass customisation experience and its consequences.

Mass customisation as a fashion business model

According to Guide, by proving people will pay more for their personalised clothes, businesses can compensate by selling fewer clothes for more money, rather than selling more units of disposable clothing for less money.

He points out that no business will adopt a practice that will hurt its ability to compete, or hurt its investors.

According to the researchers, the solution is also practical because the technology currently exists to allow many people to personalise their products online. For instance, customers can upload their pictures to a website to review different sunglass styles, or virtually try on clothes.

However, the researchers add, that equally important, flexible manufacturing technologies exist to support such product customisation at a mass scale. 3D printing as an example, and various other automation technologies that make one-of-a-kind, serial production possible.

Alptekinoglu expects the economics of such technologies, which are constantly improving, will naturally point the fashion industry toward mass customisation.

Fast fashion, overconsumption and the industry's burden

Overconsumption can be better understood through the vicious loop set up by the fast fashion industry. The rapid production of cheap clothing that is advertised as seasonal ranges and must-haves by brands encourages people to get their hands on everything. This idea of staying “in-trend” leads to mindless consumption of clothing.

The problem doesn't end here though. Guide's definition of fast fashion refers to how the fashion industry often produces clothes made of inexpensive, plastic-based synthetic materials called polymers.

"Because the clothes are cheap and tend to wear out quickly, consumers are more likely to throw them out and buy new instead of attempting to repair them. The clothes typically end up in landfills and the chemicals that make up these cheap polymers can infiltrate the water supply."

He adds recycling is often not an option either because the polymers are often too complex to efficiently recover.

In spite of this, Guide says the research team’s unique interdisciplinary approach — in case of the research study, joining supply chain with marketing scientists together — will be helpful in investigating solutions to fast fashion’s environmental impact.

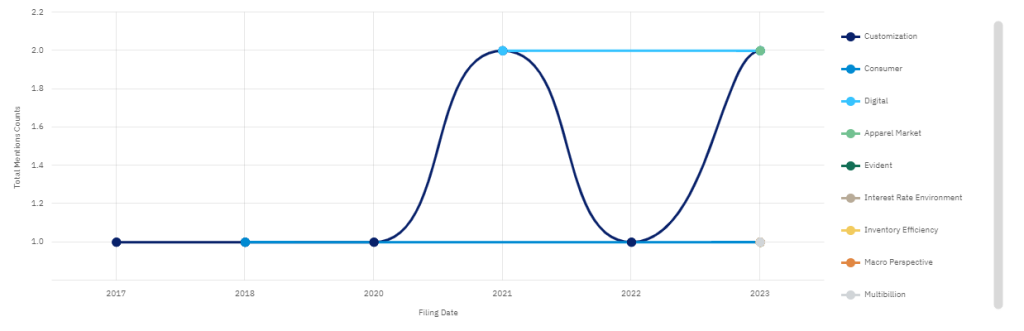

'Customisation' key word doubles in mentions between 2017 to 2023

Apparel company filings data by GlobalData shows the keyword "customisation" was used twice as much in 2021 as opposed to 2017 in the apparel industry. However, it dipped in 2022 to one mention and increased twice as much again in 2023.

Interestingly enough, the keywords apparel market and digital share the same place as customisation with two mentions in 2023 and digital being used consistently in the apparel industry from 2021 to 2023.

Slowing fast fashion - how is the industry faring?

Data shared by earth.org states that the fashion industry is responsible for producing 1.92 million tonnes of textile waste every year. It adds that if we continue with business-as-usual and no action is taken to reduce fast fashion waste – the industry’s global emissions will likely double by the end of the decade.

America alone is responsible for an estimated 11.3 million tons of textile waste – equivalent to 85% of all textiles – ends up in landfills on a yearly basis.

Other stats hint at the throwaway culture, noting that the number of times a garment is worn has declined by around 36% in the last 15 years with a piece only worn seven to ten times before being tossed.

The core issue remains that both excessive production and consumption result in the creation of significant amounts of waste. The surplus inventory frequently ends up in landfills, undergoes incineration, or gets exported to countries such as Uganda, where it contributes to the second-hand clothing market.

Our signals coverage is powered by GlobalData’s Thematic Engine, which tags millions of data items across six alternative datasets — patents, jobs, deals, company filings, social media mentions and news — to themes, sectors and companies. These signals enhance our predictive capabilities, helping us to identify the most disruptive threats across each of the sectors we cover and the companies best placed to succeed.