Back in 2022 whisperings emerged about the development of a platform designed to help brands and retailers identify the parts of their supply chain most at risk of using forced labour. It was exciting stuff, coming hot on the heels of the talk around the then-new Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) which would reprimand apparel firms not engaging in comprehensive supplier mapping and due diligence and drive down the risk of forced labour in apparel supply chains.

While supply chain traceability platforms mapping suppliers have been around for some time now, many demand membership and come at a cost, and, prior to UFLPA going live, signing up for such initiatives was mostly voluntary.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Following the publication of the legislation, apparel companies are required to provide evidence mapping their entire supply chains, and all entities involved including transport.

Dr Shawn Bhimani, assistant professor of supply chain management at Northeastern University, the lead involved in developing Supply Trace’s platform which seeks to – at its pilot phase – uncover any potential links between shipments and forced labour occurrences in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, explains the global crackdown on forced labour remains front and centre of conversations about apparel supply chains at the moment because according to estimates, it is a problem that has gotten worse with time.

What is driving forced labour in apparel supply chains?

“Right now we know there are 27m people in forced labour situations which is a subset of almost 50m people that are in larger conditions of modern slavery. I’m just talking about adults not even children. That number is the highest at any point in human history and it continues to rise with every estimate.”

He says to some degree it was exacerbated by the pandemic with people having “more vulnerabilities come to them.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“But in reality it’s a system that thrives because it lives in a hidden part of society.

“Slavery was previously known to everyone. Now, forced labour, as it exists as a form of human trafficking, is harder to detect and remediate. It continues to grow rampant in countries like India and China where you have state-imposed forced labour. That’s not to say those two countries are the only ones, many estimates report it is prevalent in every country, even the United States.”

According to the International Labour Organization’s most recent figures, forced labour in the private sector generates $236bn profit each year across the world, up 37% since 2014. The ILO explained the jump in profits from forced labour is fuelled by both an increase in the number of people forced into labour and higher profits from the exploitation of victims.

The ILO estimates there was 27.6m people engaged in forced labour on any given day in 2021, equivalent to 3.5 people for every 1,000 people in the world. Between 2016 and 2021, the total number of people in forced labour increased by 2.7m.

But how much of the spike in forced labour is being prompted by an increased appetite for cheap, fast fashion?

Bhimani concedes to some degree this is the case, together with companies pressuring suppliers for lower-cost production.

“I’d say it relates to both sides of the equation. It’s important to remember labour relies on links to corporate supply chains to survive. If these systems were not able to make money, there would be no economic reason for people to put others in forced labour.”

Is Supply Trace the missing piece of the puzzle?

I’m keen to learn how Supply Trace is working to shift the needle in terms of forced labour in the apparel supply chain.

Bhimani’s background has had a lot to do with shaping the platform. He’s not a traditional academic, in actual fact, he says, he started out in corporate America.

“I then realised I wanted to go and learn more about this problem that’s been plaguing international supply chains for decades if not centuries.”

This led to a PhD published in the British Library before Bhimani returned to the US to practice academia.

“I use my experience in corporate life in a very targeted way which is to say I try to develop research and tools for people who were in my shoes to help them do better, have the skills and toolkits they need to be able to learn about the darkest parts of our supply chains.”

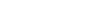

Cue Supply Trace – an open-access platform developed between Northeastern and Sheffield Hallam Universities to allow US companies, trade professionals, law enforcement agencies, and civil society to identify potential exposure to forced labour risks within supply chains.

Currently in its pilot phase, the platform which offers unrestricted access to its data, seeks to uncover any potential links between shipments and forced labour occurrences in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of China.

It leverages a comprehensive dataset that includes import, export, shipping, and customs data, complemented by publicly available trade records such as shipping and bill of lading data as well as other supply chain information as its baseline.

Employing machine learning algorithms, Supply Trace automates the process of analysing this data, tracing intricate relationships between entities. Additionally, the platform integrates risk intelligence, informed by research conducted by a team of Uyghur nationals with specialised expertise in forced labour issues within the Uyghur Autonomous Region of China.

Bhimani conducts a walk-through of the impressive, data-rich programme. Based on machine learning, it continues to improve the more it is used.

“Every time we push an update to supply trace, you see more and more facilities that are using forced labour and our risk spotlight will change because we show the most recent ones.

“The first thing it does is allow for anyone but particularly companies in the apparel trade to start their due diligence process, especially if they didn’t have access before, and understand that some of their suppliers are connected to these facilities.

“The second thing it does is automate the scanning of import records into a country where consumers are buying products.”

This, he says, provides visibility into facilities where risk lies – a task that is near-impossible for a human being to do.

“It’s automating a task that would’ve taken researchers in the past thousands of hours per supplier.”

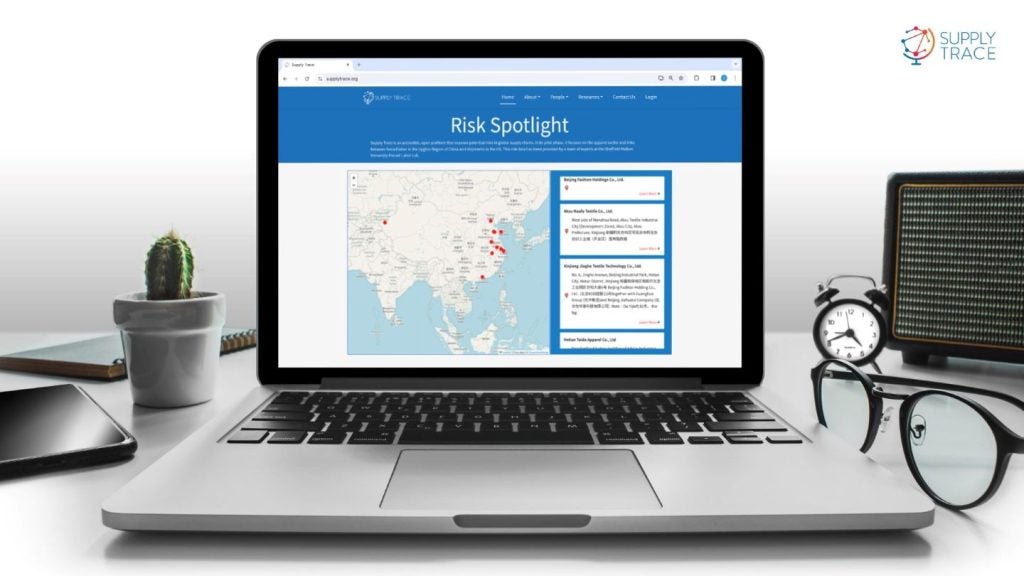

The data can then be sorted and viewed in chart form or maps for a visual representation of the at-risk areas in the supply chain. Bhimani punches in search terms for Xinjiang cotton at which point an array of spots across the US light up. Once a spot is clicked on, more details are given about the company and supplier profiles to allow the user to learn more.

What will be particularly useful is using the platform to justify concerns of third-country pass throughs.

Bhimani points to a retailer using a Sri Lankan garment supplier before demonstrating the point of origin for those textiles is actually China.

Arming the apparel sector with the tools needed to fight the problem

But, he asserts, the platform isn’t intended to name and shame.

“I’m a former corporate person. This platform is for people I wish the best for – a provision of information so they can make changes in their supply chain. This is not a naming and shaming platform and nowhere on this platform will you notice anything that says these companies are using forced labour.

“And there’s a very specific reason for that; I’m not trying to shame these companies. I’m trying to empower them to change the way they do things. Until now they haven’t had a way of knowing they carry this risk in their supply chains and where; now they can see that quite easily, but they can also access the table of the several hundred customers in the same boat as them. And they can start to make a change individually as well as together at the tier one, tier two levels and beyond.”

While currently this is filtered to only include apparel companies, at some point in the near future, the platform is designed to cover all industries.

“We’re doing one sector at a time and being very strategic about how we do it. We want it done well. We want to start in a place we know it is needed.”

The emergence of several pieces of legislation requiring brands and retailers to be accountable for the happenings in their supply chain was a significant catalyst for the launch of the platform at this time.

Beyond this, Bhimani explains access at a very large scale to international apparel data has “really been missing from this space.”

“And now it’s come into fruition alongside machine learning that can actually read all of that; massive amounts of data and machine learning that can actually crunch it.”

While he argues legislative requirements have been around since the 1930s, he says they’ve “never really been activated”.

“It wasn’t until 2021 that we saw international law actually enforce significant pressure on global supply chains.

“So that together with machine learning and data accessibility answers the “why now” part of it. I don’t think companies can do what is required of them in a meaningful and robust way; there’s no other tool out there to help them. We’ve created this platform because it needs to exist. It has to exist to create change.”

Bhimani is keen to reiterate the platform is in its pilot phase and continues to improve as it develops. While the apparel sector is the so-called “test-phase”, there are plans to open it to other sectors and geographies in future.

Apparel was an easy selection because of the growing requirements for brands and retailers to comply.

“We’ve not decided what or where [to expand to] yet. Wherever we focus on next in whichever sector will require us to not only open up the data we already have but also to pair with the experts in that region, similar to what we did in the Uyghur region to ensure it is based on voices of credibility, authority and expertise.”

Creating systemic change through transparency

So far the platform has been well-received by users. Being open-source, it is available to anyone, anywhere.

“We came at it from a simple perspective of trying to make this part of their due diligence toolkit. Specifically, it points out to apparel companies where their risks are. And it’s not just them that need to be aware of it but regulators, consumers, everyone has access to that same data now. And it’s time all of us should do – and now can do – something about it.

“The response has been overwhelmingly positive; it gives everyone a starting point. Yes, several dozen platforms might do something similar. But those are locked behind extremely high paywalls most companies, people, journalists and government stakeholders can’t really access.

“For most apparel companies, this gives them a place to start. Particularly for SMEs who’ve been lost – hit with regulation but no tools they can access to make the necessary changes. That gratitude and appreciation from the industry has been encouraging for us and given us the boost we need to keep building on it.”

Going forward, Bhimani says his ambition for the platform is that it makes a difference in the longer term to drive down those painfully high forced labour statistics.

“I think how we create systemic change is when we have that visibility in the supply chain; when we can see where things come from, who the human beings are behind where those things were produced and that leads us to make different choices. The research tells us that. The reason for that is because origins matter. And when we’re making origins public knowledge, then all of a sudden people want to make better choices. And that’s what will drive real change.”