The use of artificial intelligence (AI)-style ‘sewbots’ that can replace human sewers and other robotics look set to transform the apparel supply chain and facilitate reshoring or near-shoring to developed countries currently reliant on lower income outsourcing hubs, maybe thousands of kilometres away from buyers.

Online merchants and small new brands owned by millennials are already driving reshoring by claiming it involves a lower environmental footprint through reduced transport and less inventory waste. However, larger brands baulk at the investment and operational costs.

Palaniswamy ‘Raj’ Rajan, chairman and CEO of Softwear Automation, based in Atlanta, Georgia, US, whose sewbots can manufacture t-shirts in a fully automated process, warned that major and more established brands will remain “laggards not leaders” in technologically-driven reshoring.

They will wait for a critical mass to develop reshored production, before taking the plunge and disrupting established supply chain routes to market, he predicted.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology within the apparel sector

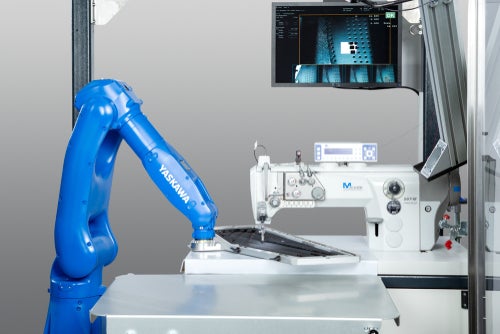

But, stressed Rajan, the artificial intelligence (AI) technology that can deliver this vision is becoming available for the apparel sector: “Our sewbots take cut fabric pieces as input, then put them through a series of automatic steps, and output a finished t-shirt,” he told Just Style.

He explained that software automation technology is a combination of “proprietary advanced robotics, computer vision, AI, and IoT [internet of things] technologies” enabling on-demand production at scale. A t-shirt can be made and dispatched within 48 hours, he said, reducing transport costs, waste and pollution.

At present, 98% of t-shirts imported into the US are made by cheaper overseas labour: “We want to shift that,” he said. “We want to make a billion t-shirts in the US in the next decade. The sustainability issues in the textile industry are horrendous and automation and onshoring could solve these problems.” His company’s systems enable manufacturers to hold zero inventory and not make anything until you get an order.

Ironically, given the lower costs that drove offshoring, Rajan predicted that there will be a segmentation of the industry between high price products best made manually, maybe offshore, and “automation for high volume, low price items and that’s where onshoring can be a real benefit”.

The most obvious and immediate vulnerability highlighted was multinationals’ over-reliance on China-made intermediate inputs and production, said the ILO. It confirmed the pandemic and its supply chain disruption “lent urgency to the discussions on reshoring and nearshoring and the restructuring of global supply chains more generally”, which included a deeper assessment of automation.

The report, ‘Robotics and reshoring Employment implications for developing countries’ stressed that this process could be bad news for outsourcing countries that have leveraged clothing and textile outsourcing to deliver economic growth. Should automation technologies substitute relatively cheap manual routine work, “the comparative cost advantage of developing countries in global supply chains could be eroded, and this could result in more and more reshoring of production and jobs to advanced countries,” said the ILO.

It cites statistics from 2016 research indicating textile, apparel and footwear workers in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region are at a high risk of losing jobs to AI-based automation, from 64% of workers in Indonesia to 86% in Vietnam and 88% in Cambodia.

That said, they are protected to some extent by the “fundamental impediment” posed by technical issues to full automation in the apparel industry: “This results from the pliability of fabrics, pieces of which need to be accurately aligned before they are sewn, something the human hand and eye can readily accommodate but which poses daunting challenges for automation,” stressed the report. This challenge is exacerbated by the vast range of apparel products, the rapid changes in product demand (witness fast fashion), the varied properties of different fabrics, and the range of sizes.

But challenges are opportunities to the truly innovative. Take Sewbo, based in Seattle, US, which uses a mix of AI-style robots and sewing machines to create t-shirts by temporarily stiffening fabrics to enable robots to “build” garments, as if they were working with metal, said a company note.

“The fabric panels can be easily moulded and welded before being permanently sewn together” by “off-the-shelf robotics”.

Sewbo’s water-soluble stiffener is removed at the end of the manufacturing process with a rinse in hot water, leaving a soft, fully assembled piece of clothing and the stiffener can then be reused.

“Such re-programmability could, in principle, accommodate the rapidly changing demands of the fashion industry,” said the ILO report.

A separate ILO report, published last May (2020), called ‘Automation, employment and reshoring in the apparel industry Long-term disruption or a storm in a teacup?’ highlighted the fact that automation can be used to efficiently produce small quantities of products “in a way that labour-intensive processes would not be able to do. In this context, meeting demand for customised goods could propel automation in apparel and footwear manufacturing”.

Rising transportation costs together with the current fuel hikes and international logistics issues are creating the “perfect storm” to drive reshoring initiatives, textile consultant Michael Sanders, of Digital Bias Consulting, based in California, told Just Style.

“We’re at a tipping point,” he said. “And automation is the silver lining. We should get back to making great products in a greener way. It just needs our government to say they want the jobs back and we can have the industry back here,” he suggested.

“We have the most expensive labour force with the oldest equipment but with new equipment, you don’t need as much labour so we can pay high wages meaning it wouldn’t make sense to do it anywhere else. Everyone’s looking at what they can do the best locally.”

Sanders said if the US apparel market was based onshore, there would be less reliance on its export business as well as imports and such a transformation would “change the whole supply chain picture”.

However, Patrick Van den Bossche, partner and global advanced analytics practice lead at global consulting firm Kearney, which publishes an annual reshoring index, said bringing back apparel and textile manufacturing to the US needs to be approached from “a cross-value chain perspective to get a full view of costs, etc. to identify opportunities”.

He told Just Style: “There’s a high degree of non-value added, labour intensive steps in each stage of the value chain, as well as between steps in the value chain, for example material handling. That’s especially true for cut and sew, where most operations only have about 20% ‘active’ time while the rest is non-value added. These inefficiencies need to be leaned out, automated or cut out altogether.”

The cost of refitting factories capable of full automation also needs to be taken into consideration by manufacturers considering onshoring or near shoring to lessen costs elsewhere in the supply chain, he noted.