As apparel retailers and brands scramble to try to disentangle their cotton supply chains from possible links to forced labour abuses in Xinjiang province, China is likely to be looking for alternative markets for its fibres – presenting new challenges for countries like South Africa.

Allegations that ethnic minority labourers in the Xinjiang region in China – which produces 85% of the country’s and 20% of the world’s cotton – are forced to pick cotton by hand through state-mandated schemes first surfaced more than a year ago.

The claims have potentially devastating consequences for global supply chains that use the region’s cotton as a raw material.

In January, the British government indicated it was going to tighten up controls regarding imports from the Xinjiang region and that companies will have to publish supply chain transparency reports or face the risk of being fined. And Canada is also urging firms to review their supply chains for Xinjiang inputs.

The US has gone one step further, issuing a withhold release order (WRO) detaining imports of cotton products – including apparel and textiles – if they’re suspected of touching Xinjiang forced labour at any point in the supply chain.

But for countries like South Africa, which has a close and tight diplomatic relationship with China, the chances are slim that there will even be a mild rebuke regarding China’s alleged human rights’ record or practices.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataForced-labour product to seek alternative markets

“Given that the South African government has been unsuccessful in even addressing illegal, undervalued clothing imports from China over the last two decades, to expect them to control the origin of the cotton content of clothing originating from China is, I suspect, a rather forlorn hope,” says Brian Brink, executive director of the Textile Federation (Texfed).

Furthermore, Brink believes a consequence of the US’s embargo on cotton goods from Xinjiang is that increased volumes of forced-labour produced product will be seeking alternate markets throughout the world.

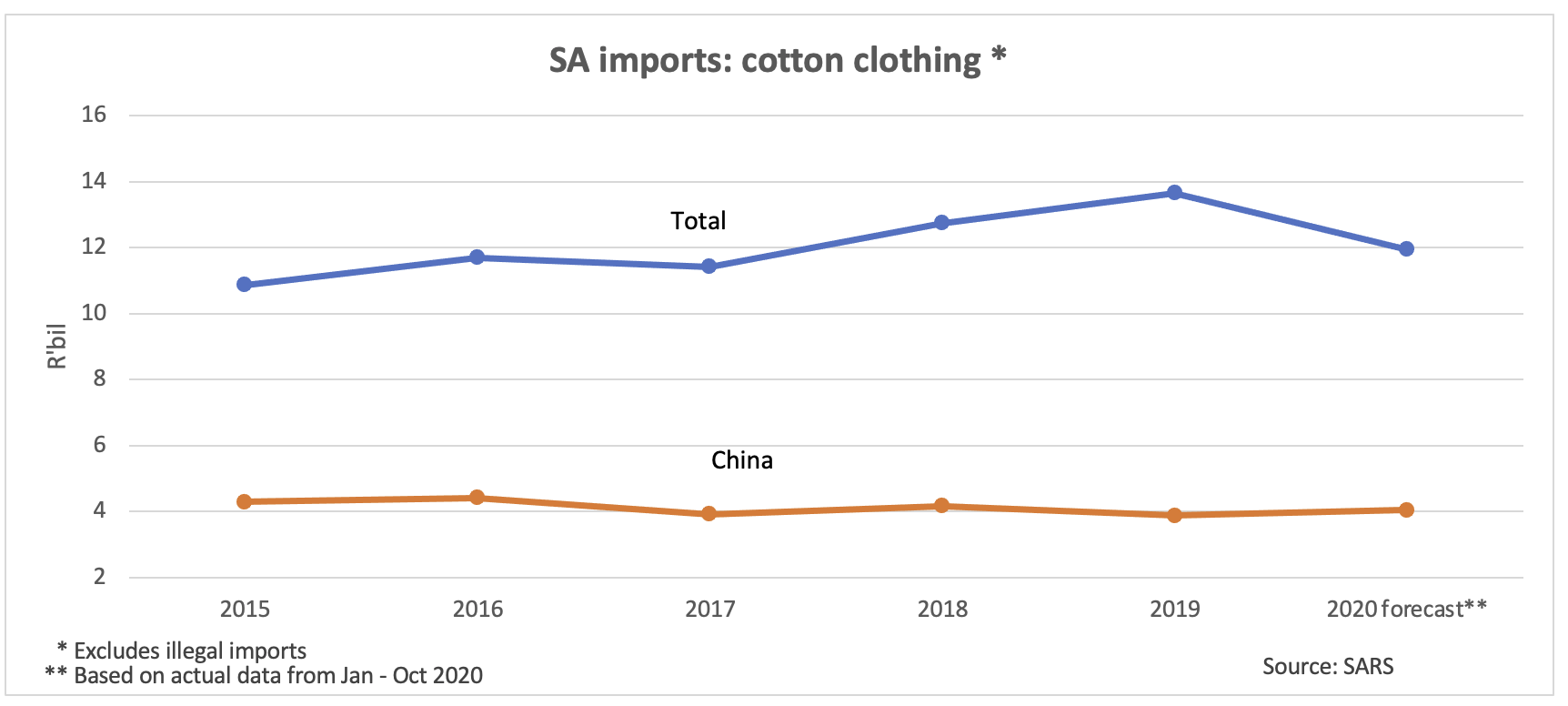

This, of course, does not bode well for South Africa where illegal, undervalued clothing imports are already a big problem.

Paul Theron, acting executive director of the Apparel Manufacturers of South Africa (AMSA), says it is a complex issue with apparent allegations, but no proof – although the industry is highly suspicious of China’s practices.

Local clothing retailers

South Africa’s prominent clothing retailers – including Woolworths, Mr Price Group, Pepkor, The Foschini Group and Truworths International – were approached for comment on the policies they have in place regarding the raw cotton used in their merchandise.

According to Woolworths spokesperson Silindile Gumede, the group has no supplier relationships in China’s Xinjiang province and does not source finished garments made using slave labour from the region or from North Korea.

“We audit our suppliers via independent third parties to ensure that the group’s own Code of Business Practices is upheld and are committed to partnering with suppliers and industry stakeholders to protect and improve conditions and promote worker empowerment. Woolworths does not under any circumstances tolerate forced labour, and we will act quickly to address unjust labour practices should concerns arise within our supplier base.”

Pepkor – the holding company of retailers like PEP and Ackermans – says its sourcing office in China follows a process that includes inspecting and rating compliance levels of suppliers on a bi-annual basis to ensure that the group complies with the necessary labour laws and regulations across its value chain. The group says none of its retailers source from Xinjiang province.

The Mr Price Group, The Foschini Group and Truworths International did not respond to the request for comment.

Cotton value chain is highly complex

One of the biggest challenges in identifying cotton originating from the Xinjiang region is that cotton is a generic fibre. “And as China is also a major importer of cotton, it becomes even more problematic in identifying the source of fibre once blended and processed further,” Theron says.

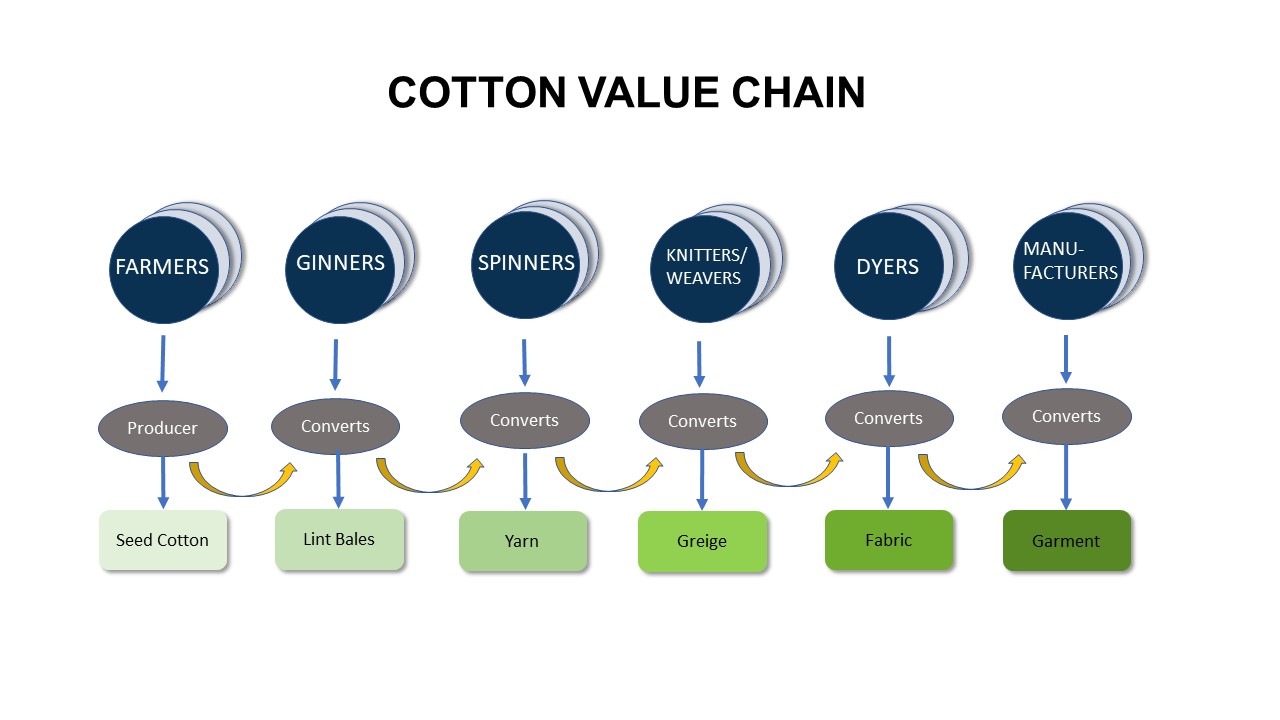

The cotton value chain is highly complex, with blending of the product happening as it makes its way through the value chain. This makes it difficult to identify the original source of the raw cotton picked on the farm, in the final manufactured product. This means that, for instance, a cotton T-shirt that says it is manufactured in China, Bangladesh, Eswatini or South Africa, can include raw cotton that has its origin in different cotton-growing regions and countries.

The blending of cotton happens at the spinning process, where lint is converted into yarn, at the knitter/weaver where the yarn is converted into greige fabric, and even at the manufacturing stage: for instance in the case of a pair of cotton trousers, where the inner lining of the pockets can be made from different cotton than the outer shell.

Even though cotton is grown in South Africa, the country lacks spinning capacity, meaning that most of the lint cotton is exported for processing and manufactured into clothing items, before being imported again.

Retailers can do more

Retailers can do more

Despite the difficulty in tracing the origins of cotton used in manufacturing the final product, Thomas Robbertse, founder and executive director at iQ Logistica – the agtech company that developed the cloud-based SCC Operations Visibility Platform that integrates local cotton supply chains – says retailers can do more regarding the visibility of their supply chains.

“Technology like ours allows for greater visibility of supply chains right through, from the farm to the customer. However, in order to function optimally, it is essential that every role player in the supply chain commits to the process.

“It is good and well to claim that there are no abusive labour practices, or for that matter also any sustainability shortcomings, in one’s supply chain, but the only way to instil confidence, is to prove it, which traceability platforms like ours facilitates.”

Offer full traceability

The Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) – the largest cotton sustainability programme in the world which locally includes Woolworths and Pick n Pay Clothing as its retail members – says legislation requiring businesses to demonstrate knowledge of their supply chains is becoming more common around the world.

Companies are not only being asked to know more about the origins of their materials but also about the conditions under which they are produced.

“Increasing media and academic attention on geopolitical issues, including the treatment of Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang area of China, has further demonstrated that production location and sustainability are crucially interlinked,” says Amy Jackson, BCI director of membership & supply chain.

Up to now, the BCI has made use of its Chain of Custody (CoC) framework that incorporates the concept of “mass balance” – a widely-used volume-tracking system that allows Better Cotton to be substituted or mixed with conventional cotton provided equivalent volumes are sourced as Better Cotton.

However, it has halted all field-level activities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of China after acknowledging “an increasingly untenable operating environment.” And work is underway on a new Chain of Custody (CoC) solution that will go beyond this mass balance chain of custody model and offer full traceability of its cotton by 2022.

“As our world progresses, we recognise that it is time to explore going beyond this mass balance CoC model to offer full traceability and even more value to Better Cotton farmers and companies. For Better Cotton, this means that, at minimum, we seek to determine the region in which the seed cotton was produced and identify the businesses involved in its transformation to a finished good,” Jackson adds.

Loss of capacity and skills in cotton value chain

While South Africa’s cotton industry has experienced solid growth in the last seven years, the country still lacks the capacity and skills within the value chain to take full advantage of local beneficiation.

This means that most of the land’s lint cotton is exported for processing before the final product is imported again. This translates into an opportunity loss of about ZAR20.4bn (US$1.35bn) of beneficiation in the local cotton value chain based on the 2018/19 production year’s output of 51,000 tons of lint cotton.

The country’s cotton production has grown by almost 800% since 2013 following the establishment of the South African Sustainable Cotton Cluster (SCC), which was funded by an initial grant of ZAR200m from the Department of Trade and Industry.

84% of cotton lint exported

Although local cotton ginners have up to now been able to absorb the surge in cotton production, South Africa does not have the spinning capacity to convert the lint into yarn, meaning that around 84% of lint cotton has to be exported.

According to IQ Logistica’s Robbertse, the set-up of a cotton spinner is very capital intensive, costing anything from ZAR1bn upwards to install.

“Despite the number of ginners declining from 24 in the heyday of local cotton production to the present seven ginners, it is still able to accommodate the cotton that is currently farmed. However, South Africa lacks spinning capacity meaning that most of the lint cotton is exported for processing and manufactured into clothing items, before being imported again.”

Employment opportunities lost

Robbertse says in 2019 cotton lint left South Africa’s shores at about ZAR24/kg, whilst the finished product was imported at around ZAR500/kg.

“Based on the export of about 42,840 ton cotton lint and the concomitant value loss of ZAR476/kg (ZAR500/kg – ZAR24/kg), the opportunity loss in local beneficiation to the economy comes to roughly ZAR20.4 billion. Not to mention the many potential employment opportunities that have gone wasted.

“But even if we were to build spinning capacity in South Africa, there would still be a huge skills shortage because of the demise of the clothing textile industry over the last 30 years brought on by trade liberalisation and global competition, which unfortunately also led to cheap imports.

“This all means that were we to establish spinners in South Africa, we would still have to import skills from Asia that could then also train local labour in the trade.”

But according to Robbertse, it is not all bad news as the export of cotton lint does earn the country important foreign exchange and helps farmers to offset some of their input costs like fertilizer, fuel and equipment that are all dollar-based.